When Mythmaking Refuses to Yield to Reality

Two new books by acclaimed authors show their shortcomings as they try to valorize sociopaths of Silicon Valley.

Walter Isaacson and Michael Lewis have no problem selling books. They’re bestselling authors many times over, and when they have a new book to publish, the industry lines up and accepts it without question or debate. Each man also found his niche. Isaacson became a biographer of “great men of history” with his books on Benjamin Franklin, Albert Isaacson, and Steve Jobs. For Lewis, he loves tales of outsiders who have a way of seeing the system in a way no one else does, thus upending it (Moneyball) or avoiding its coming catastrophe (The Big Short). While these descriptions don’t cover the totality of these author’s bibliographies, it is what they’ve become known for and a perspective they have no issue returning to.

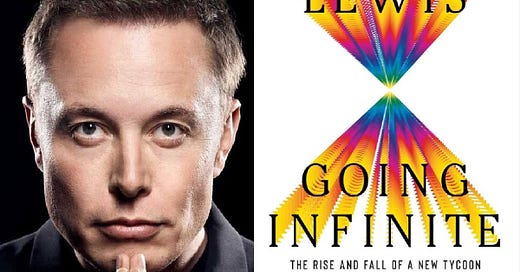

They both released new books this fall. Isaacson had a biography Elon Musk, and Lewis had Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon, which centers on crypto magnate Sam Bankman-Fried. Both books have received pans as reality collided with the subject, and these authors, rather than reassess, doubled down on their reporting and perspective. Isaacson went so far as to take the “L” on behalf of Musk when, after the book said that Musk endangered Ukrainian troops by cutting off their Starlink access, Isaacson said that Musk had never enabled it in the first place, once again accepting Musk’s version beyond even his own reporting. For Bankman-Fried, Lewis insists that the former head of FTX, who is now on trial for fraud, is misunderstood. “The full story will do violence to their mental picture,” Lewis tells The New York Times. “It’s been marvelous to me to watch people who know a fraction of what I know, who are willing to be much more certain than I am about what happened. I’ve earned my doubt. You haven’t yet earned your certainty.” I’m sure people who research vaccines online would say the same thing.

These books are fascinating not because of the insights they try to provide into their subjects, but rather what they reveal about their authors.1

The Great Man of History

Based on reviews and excerpts I’ve read of Elon Musk, it’s clear that Isaacson went into this thinking he had another Steve Jobs on his hands. And to be clear, it’s not that Musk isn’t worthy of a biography. Regardless of one’s feelings about him, he is the richest man on Earth, and has pushed for transformation in the electric vehicle and space exploration arenas. To say he’s inconsequential would be erroneous.

However, Isaacson wants to make the connection that because Musk has accomplished great things, he must be a great man. That doesn’t mean likable or even moral, but possessing some kind of genius that the rest of us don’t possess, which has allowed him to amass wealth and power. In this way, Isaacson sees Musk as the beneficiary of a meritocratic rise where the only way to explain his achievements is that he earned them.

Isaacson doesn’t want to investigate how much the playing field is already tilted in Musk’s favor. This would require Issacson to investigate the economic conditions of apartheid South Africa where Musk was raised, or push back on Musk’s claims that wilderness retreats for young, white, affluent South African boys always resulted in at least a death or two. Isaacson also tries to humanize the young Musk by arguing that his outlook on the world was shaped by an abusive father (and to be fair, his father is super gross) and bullying at school (although sometimes Musk was the bully). Hence, a crucible of a wealthy kid who is on the spectrum goes on to create the future.

I think Isaacson would have been more than happy to write a book about a guy with dubious technological accomplishments, and gloss over the bits like where the Teslas don’t work and they try to cover it up or promising a high-speed tunnel but never delivering one. But Musk’s public purchase of Twitter really throws a work into the wrench of painting the guy as a genius when he cannot stop posting. Musk bought the social network on a whim, didn’t do his due diligence, and couldn’t back out of the deal even though he wanted to.

This is not a great man, so Isaacson has to resort to another kind of archetype: the keen gambler. He then resorts to an anecdote about Musk playing poker without understanding that Musk is very bad at poker. What Isaacson cannot admit is that the game Musk is playing is rigged. He cannot grapple with the fact that Musk was born wealthy, born into a society that extended him greater privileges because of the color of his skin, and then got lucky in spite of himself so that his fortune kept growing at an exponential rate.

I guess I can’t blame Isaacson too much, because the alternate conclusion to “Elon Musk: Masterful Gambit, Sir” is that an obscene amount of wealth isn’t something you achieve because you’re a genius or a pioneer or a maverick. It’s more a confluence of societal factors and dumb luck. It’s nice to think that we all possess agency and ability to achieve great wealth, but we know that’s not the case. Does Musk work hard? Sure, but lots of people do, and most of them aren’t billionaires. Also, books sell when their main figures are active and make the case for their success, and Musk actively works against that. Rather than reset and ask if Musk was really worthy of the same framing as Albert Einstein or even Steve Jobs, Isaacson forged ahead to burnish an image that doesn’t uphold its raison d’être.

Fraudulent Premises

A similar problem befalls Going Infinite. When Lewis started chronicling Sam Bankman-Fried, a lot of people were getting high on the crypto future Bankman-Fried was selling. I’ve written about how celebrities didn’t need to burnish this image, but Bankman-Fried was all about image. Lewis seems in awe of this guy who wears a t-shirt and cargo shorts wherever he goes and doesn’t have the patience for a suit unless absolutely necessary (e.g. lobbying congress). He plays video games while half-paying attention to a video call with Anna Wintour! Wow! But hey, money talks and Bankman-Fried was had amassed billions of dollars in the crypto market. What could go wrong?

The section of the book where you can tell Lewis is most enamored of Bankman-Fried is when he’s applying and working for the trading firm Jane Street Capital. Perhaps this is because it falls in nicely with material Lewis had covered before—High Frequency Trading in Flash Boys—but he also just seems impressed by how fast Bankman-Fried can suss out probabilities. It all falls in neatly with how Lewis thinks about Bankman-Fried, which is as a young man who thinks too much but feels too little. It’s a familiar archetype of the loner who’s so far inside his own intellect that he has difficulty relating to others.

But even a cursory reading of Going Infinite shows Bankman-Fried as a man who feels and thinks too little. He disdains any kind of art and humanities because they don’t have “answers.” He is incurious as a point of pride feeling at the ripe old age of 22 that he never needs to read a book or interrogate his own beliefs. He seems (not uncommon for guys in their early 20s) that he has it all figured out, and that people just need to get out of his way.

His actions also demonstrate immaturity as he frequently will not show up for events or meetings or pay full attention to people trying to have a conversation with him. For Lewis, this is a sign of brilliance, a man so focused on his goals that he simply does not have time for the minutiae of acting in a professional manner. However, something tells me that if a young woman wanted to stroll out on stage wearing a t-shirt and cargo shorts, she would not be afforded the same kind of awe and reverence afforded Bankman-Fried’s devil-may-care attitude.

Of course, this kind of interrogation of larger societal factor is beyond Lewis. He never stops to think about why Bankman-Fried has exceled. Lewis doesn’t even think that deeply about the crypto market (in a footnote, he explains that he has tried to understand crypto, but has never fully wrapped his head around it; he dismisses his lack of knowledge by noting that Bankman-Fried didn’t fully understand crypto either, but knew it was a burgeoning market he could conquer). Lewis is so wedded to his narrative about the young, aloof genius that when reality crashes in, the book still can’t seem to give up the belief that Bankman-Fried was running a grift.

In the book’s third act, the walls quickly come crashing down, and everyone is left scrambling as FTX, Bankman-Fried’s crypto exchange, collapses, and the courts come for him. Even here, Lewis thinks he’s just smarter than everyone else, snickering at the lawyer now in charge of a bankrupt FTX for not understanding Bankman-Fried as well as Lewis does (or at least thinks he does). Lewis seems enamored of his own inside knowledge, which he has demonstrated in interviews since the book’s release. In an interview with Time Lewis says:

“You get up, you tell one story, and they tell the other story, and the question is which story the jury believes.” I’m in a privileged position to tell a fuller story, without leaving out any of the nasty details. If I were a juror, I would rather hear my story than either defense or prosecution.

And yet just last week, FTX co-founder Gary Wang admitted in court that Bankman-Fried directed him to build a secret backdoor in FTX’s code that allowed Alameda Research (Bankman-Fried’s trading firm) to siphon money away from the exchange. Nowhere is this mentioned in the “fuller story” of Going Infinite. The picture of Gary Wang is a genius programmer who never speaks. That’s it. And maybe that’s accurate, but it’s clearly not the full account, and Lewis didn’t dig deep enough to know it. Lewis also seems incredibly comfortable with the fact that Bankman-Fried was having a romantic relationship with Caroline Ellison, the CEO of Alameda, but that this relationship was kept secret from all employees despite posing a clear conflict of interest.

The title of the Times interview with Lewis is “Michael Lewis Doesn’t Do Villains,” but he clearly doesn’t do journalism either.

Tech Wizards

Walter Isaacson was born in 1952. Michael Lewis was born in 1960. They’re both well educated, and both came to prominence as authors in the early 90s. But look at how fast technology has changed in the last thirty years, and it’s clear that neither author can really make heads or tails of the world as it is now, so they try to force it back into a familiar framework that worked in previous decades.

I fully admit that tech can be daunting. But it’s not magic. It’s math, coding, programming, and science. And yet it seems like both Isaacson and Lewis were reluctant to delve too deeply into Silicon Valley and understand its intricacies. They felt confident enough that they understood not only people, but people who accomplish “great things” where “great things” means “a grotesque amount of wealth.” And at no point, did either author seem to check their underlying assumptions. They looked at the tech industry as a business like any other and assumed that the success of Musk and Bankman-Fried meant they had won a fair game through intellect and grit.

What’s galling is that even after gaining a closer look, neither author could be bothered to take a step back and question the book they were writing. Neither man needs to publish as they’re both well-established. In his Times interview, Lewis even brags that, “I always leave myself with walkaway-ability,” but later notes that he had only eight months to publish Going Infinite because his agent pitched the movie rights, and Apple snapped them up for $5 million. But Lewis says that wasn’t a problem because he writes his books quickly (of course, if new information is being revealed at a trial, maybe, I don’t know, pump the brakes?)

So instead of seeing Musk and Bankman-Fried as easily-distracted guys or investigating what it means if they’re on the spectrum (the creation of a stereotype that seems to argue people are on the spectrum are brilliant but callous with other people’s feelings as if people with autism can’t be kind), Issacson and Lewis sit back in awe at how these guys make so much money while also being obsessed with video games (The Battle of Polytopia for Musk; Storybook Brawl for Bankman-Fried). Again, any interrogation of the premise—are video games a distraction? Are they a sign of a wandering mind?—would be worthwhile. After all, video games are great, but they are typically a recreational activity, so where do these workaholics find the time? Instead, the obsessive playing of video games becomes a marker for how these protagonists see the challenges of the world. They’re guys who think chess is too boring, and need video games because video games keep changing the rules. The implication is, “You think chess grandmasters are smart? Check out these guys!”

Of course, they’re not that smart. Musk is a walking punchline because he’s both addicted to Twitter and can’t stop fueling its worse tendencies. Bankman-Fried is looking at life in prison because he thought he could swindle the world on a crypto bubble that was obviously going to pop. They’re both extremely proud of their lack of curiosity because it’s a marker of their narcissistic tendencies. What makes these two men interesting isn’t their personalities or their wealth, but that the world revered them in the first place. Isaacson and Lewis adopted that reverential stance, and even after a deluge of evidence to dissuade them from their original stance, they couldn’t let it go. Walter Isaacson needed Elon Musk to be great. Michael Lewis needed Sam Bankman-Fried to be great. And if they’re not great, then what does that say about Walter Isaacson and Michael Lewis?

Recommendations

Today is a Prime Day sale so I’m just going to list five 4K discs that are on sale that I think you should add to your collection. The sale is good for today only, so I suppose that’s a benefit of opening this Substack when it hits your inbox!

Jurassic Park ($10.99)

Casablanca ($11.99)

Singin’ in the Rain ($9.99)

Apollo 13 ($10.44)

Inglourious Basterds ($10.99)

I’ve basically refrained from chiming in on social media about the War in Israel, and the latest Substack from Talia Levin does a good job of explaining why. Here’s a quote that’s stayed with me:

There’s a war in Israel and Gaza, and the left-wing orthodoxies and right-wing orthodoxies of the moment — each in their own way advocating or excusing the slaughter of unarmed civilians and whole towns — stream past me in impossible numbers, interleaved with videos of violence, with outright propaganda, with full-throated advocacy for ethnic cleansing. In this moment of peril, in which people I love are in real danger, the doubled self is present in its dark mirror. I feel the urge to speak meaninglessly, and the urge to stay silent, and the senseless notion that not speaking is the same as refraining from action.

It isn’t. I am not an expert on Israel or security or warfare or Hamas or Fatah or the Netanyahu government or the broader geopolitical landscape of the Middle East. What I cling to are the idea that children should not be slaughtered for the sins of their governments, and that I want the people I love to be safe; this is the sum of my opinions. The carefully constructed digital self I have spent a decade building is null in this moment, as are so many things in the face of so much death. Every day since this began I have recited Psalm 25 — “Mine eyes are ever toward the LORD; for He will bring forth my feet out of the snare” — because the words are old and good and round and solid, and Psalms are what you say when you want lives to be spared. I pray like a child offering anything and everything as barter.

What I’m Watching

Last night I saw The Burial, which is based on the incredible true story about a small-town funeral parlor owner who, with the help of a flashy personal injury laywer, went to war with a giant burial services corporation. I’ll have more to say about the film in my Sunday issue, but for now I’ll say it’s the kind of courtroom drama that I really miss seeing. Is it an accurate representation of how trials work? Probably not! But I’ve seen legal proceedings, and they’re typically pretty boring! You know what’s fun? The way Hollywood treats trials!

The film works incredibly well because Jamie Foxx is outstanding as flashy lawyer Willie Gary opposite the soft-spoken performance of Tommy Lee Jones as his client. That’s the core of the movie, and it works wonderfully. I do think the film’s reach extends beyond its grasp when it tries to link the case—a bigger corporation using the power of capitalism to crush a tiny business—to the ills of slavery (there’s a monologue about power erasing legacy that tries to bridge the gap), but at least it doesn’t feel like a cynical reach. It’s a feel-good story where Foxx and Jones get to shine, and I wish more people would get to see it in a crowded theater like I did last night. As it stands, the film arrives on Prime Video on Friday.

What I’m Reading

While I patiently waited for Going Infinite to arrive, I read a lot of Ultimate Spider-Man trade paperbacks (volumes 5 – 12, to be precise), and they’re fun reads. They stumble a bit when they become subject to Marvel’s larger whims about trying to tie in Spider-Man to other Marvel stories, but when he’s off doing his own thing, it’s really enjoyable. Where you can see writer Brian Michael Bendis really sinking his teeth into the material is when he gets to examine the psychology of supporting characters like Aunt May and J. Jonah Jameson, and that’s to the series’ benefit since every story can’t be, “Peter Parker is miserable being Spider-Man.”

Last night, I read Bill Watterson’s new book, The Mysteries, which he co-authored with John Kascht. Watterson, for those who don’t know, was the creator of Calvin & Hobbes, and he consciously chose to end that beloved series in 1995. Since then, he has kept to himself, gaining the reputation as the J.D. Salinger of the comics world. But now we have The Mysteries, which is not like Calvin & Hobbes, but also has a similar concept. If you look at Calvin & Hobbes as something ostensibly designed for children but with much bigger ideas that adults can appreciate, then The Mysteries exists in the same vein. It reads like a children’s book, but its stark images and foreboding subtext are for adults. So no, don’t expect a cardboard box that creates clones, but also this doesn’t feel like the kind of story and approach that just anyone would have made. I just hope we don’t have to wait another few decades for Watterson’s next book.

What I’m Playing

I’m still kind of waiting until Spider-Man 2 arrives next Friday, but I also found myself getting sucked into Castlevania: Rondo of Blood. It’s far more difficult than its sequel Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (one of my all-time favorite games), but I can’t deny that I’ve gotten some joy out of the frustration of grinding through particular levels and bosses. Anyway, the upside is that it’s not like I had to learn complicated controls or a complex story, so I can easily return to it once I devote my gaming time to Spidey.

I’ll note here that I’ve read Going Infinite but only read excerpts of Elon Musk because I would rather hit myself in the head with a hammer than read a 670-page Elon Musk biography.