Matthew Perry died a little over a week ago. The actor’s death was followed by a rush of memorials that examined both his famous performance as Chandler Bing on Friends as well as his lifelong battle with drug addiction. Looking at these articles, I wondered if I had anything to add, especially when Perry himself had inadverdently provided a powerful epitaph in an interview:

“The best thing about me, bar none, is if somebody comes up to me and says, ‘I can’t stop drinking; can you help me?’ I can say yes and follow up and do it,” he explained. “It’s the best thing. And I’ve said this for a long time: When I die, I don’t want Friends to be the first thing that’s mentioned. I want that to be the first thing that’s mentioned, and I’m going to live the rest of my life proving that.”

In the outpourings of grief from those who knew him, it seems like Perry did exactly that. But outside that circle, there is still Friends, and Friends is, despite its many flaws, a sitcom like few others. It’s a show that will always be relatable in that, as co-creator David Crane said, it’s about that time in your 20s when your friends are your family. For a variety of reasons, Friends is the rare sitcom that transcends generations, and people who weren’t even alive when it aired can feel right at home with these six characters.

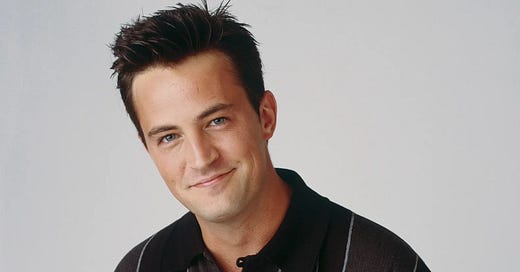

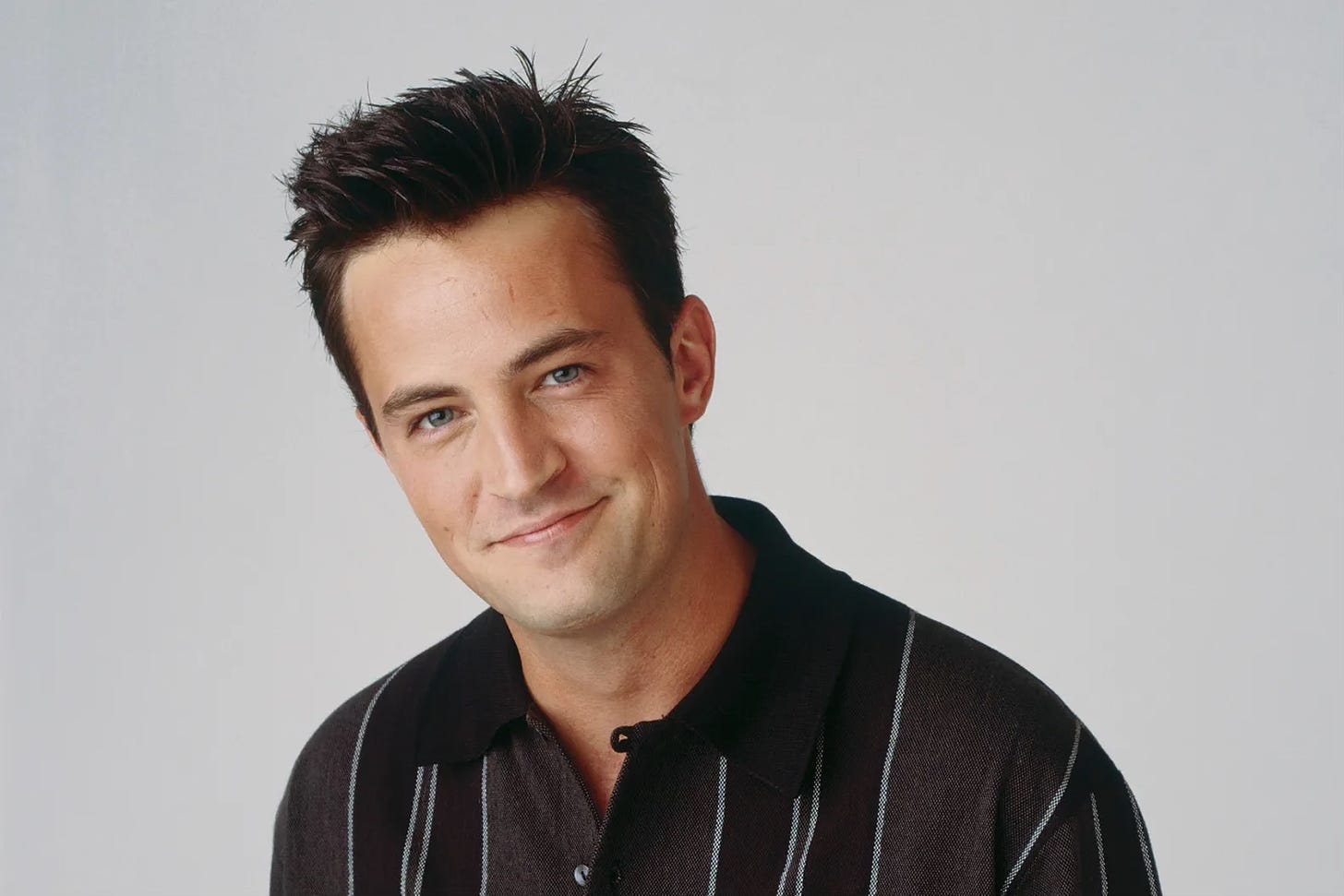

For me, Chandler Bing was my guy. The magic of Matthew Perry’s performance wasn’t simply that Chandler had the best lines (and, unlike the other five characters, Chandler is built as a quip machine). It’s that Chandler had to be handsome, funny, and painfully insecure. If Ross was the romantic and Joey was the ladies man, then it fell to Chandler to be both single and comically self-loathing about it. Chandler wasn’t a bad guy, and yes, he had the stereotypical “commitment issues” thing that male sitcom characters get saddled with, but Perry found the comic honesty in being a single guy who isn’t immediately off-putting, but also can’t get out of his own way due to his mountain of insecurities. If Joey could woo anyone with a “How you doin?”, Chandler had to first climb over his own wall of sarcastic remarks and self-loathing.

In my teens and twenties, I found Chandler deeply relatable. I had friends who were Joey-esque in that they never stayed single for long, but I was Chandler in that we were both aware of our sense of humor as both a sword and a shield. We could make people laugh, but it was also a way of trying to fight off insecurities. The joke wasn’t necessarily for a sense of camaraderie, but to prove that we were smart and witty. The magic of Perry’s performance is that he understood what it means to have enough confidence to crack a joke yet almost no confidence in your ability to relate to other people. It’s a bit of a paradox, and Perry made it look easy.

When I watched Perry’s 1997 film Fools Rush In a few years ago, I remarked that I found the movie fascinating, because it’s a “case study of why Matthew Perry is a TV actor and Salma Hayek is a movie star.” In retrospect, that seems like a bit of a putdown, but it’s really only a putdown if you think in the old Hollywood way that movies are superior to TV, and therefore its actors are superior to TV actors. But the framing I meant is one of intimacy. Salma Hayek is a movie star because her personality and charisma are so massive that they need a big screen. That’s not to say she can’t be good on a TV show, but she has that X factor that makes her electric in a movie theatre.

Perry, by comparison, despite his grand gesticulations and unforgettable line deliveries, is an intimate figure. He’s someone you want to invite into your home week after week and return to time after time. I don’t think it’s unreasonable to say that many folks have probably spent more time with Friends than their actual friends. The gift of being of a good sitcom actor is that you establish such a strong bond with the audience that they want you in their home week after week (and in the streaming era, hour after hour). Perry could, and did, do more than just Chandler (his work as Joe Quincy on The West Wing during the Sorkin era is particularly good), but trying to follow up Friends is like trying to follow up climbing Everest.

So I’m glad that Perry found rewarding work not in trying to duplicate the success of one of the biggest shows of all time, but by trying to help other people out of the darkness that consumed so much of his life. Being that light—whether it’s with a battle against drug addiction or just providing a few laughs to a lonely guy on a Friday night—is a worthwhile legacy.

Excellent